The great bounty of our nation sees us stand apart

This article by Bernard Salt (Demographer) is a must read. Do yourself a favour and not only read it for your own benefit but pass it on to anyone you care about especially your children. Bernard Salt offers not only a brilliant analysis of Australia as it is placed within this region and the world but also an insight into where the future of work and the economy will lead. Please enjoy.

Michael Arnold

Director, Town Planner, Land Surveyor

Arnold Development Consultants

The great bounty of our nation sees us stand apart

By Bernard Salt

Inquirer Newspaper (The Weekend Australian 29th April, 2017)

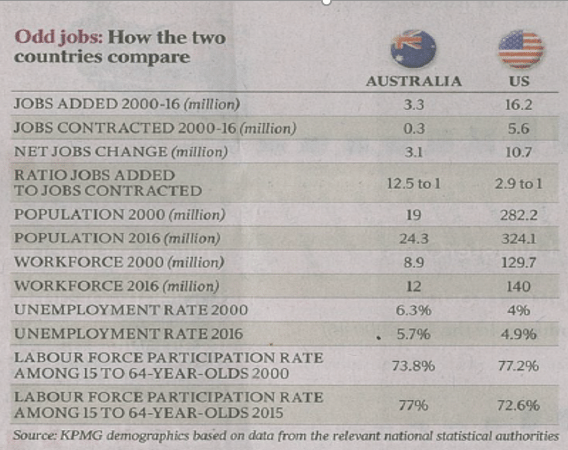

If you ever needed proof that Australia is the lucky country or that we are living in the most fortunate times, look no further than the charts and table on this page. Australia stands well clear of peer nations on a range of critical measures.

Our good fortune is not the product of brilliant political management or because of the stoic forbearance by the people – although if that’s what makes what I have to say more palatable, then so be it – but because of a simple compelling equation.

We are 24 million people sharing the resources of an entire continent and surrounding waters. No other nation on earth – not even the Americans – can make such a claim.

Our wealth is underpinned by sheer bounty of the Australian continent, including mineral resources, agribusiness and, increasingly I suspect, lifestyle – meaning property.

We have in spades what the rest of the world wants. That makes us lucky, but it also makes us vulnerable to a malaise brought about by comfortable prosperity and perhaps triggered by what I call the Trumpification effect, where disaffected voters support outliner candidates and thinking.

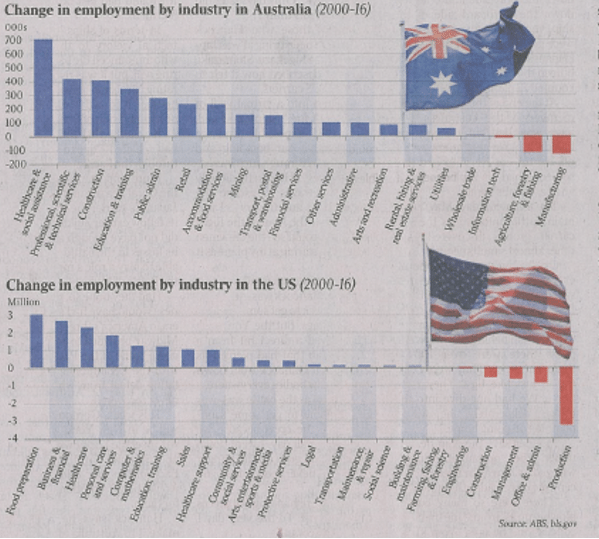

My colleague Simon Kuestenmacher and I have assembled workforce data since 2000 for Australia, the US, Britian, Canada and France. Each nation publishes annual estimates of the workforce in the various sectors that make up the economy. The number of sectors varies between countries. The Australian economy, for example, comprises 19 sectors such as manufacturing and health, whereas the French have 16 and the Americans 22.

Between 200 and last year, the number of jobs in the expanding parts of the Australian economy increased by 3.3 million whereas the number of jobs in the contracting parts dropped by 267,000. Queensland Nickel closes in Townsville: that 250 jobs lost in manufacturing. Alcoa closes in Geelong that’s another thousand jobs lost to this sector. But this also means that thus far in the 21st century for every job lost (267,000) there are 12 jobs created (3.3 million).

Of the 19 sectors that comprise the Australian economy, 16 have recorded job growth since 2000 whereas three have recorded job loss. No peer nation has generated jobs across the economy as has Australia in the 21st Century.

We are different. And yes, we even may conclude that we are special. The Australian economy added 3.1 million net extra jobs between 2000 and last year. France, a nation more than twice as populous as Australia, added a net extra 1.4 million jobs in this period. Canada, with 36 million residents added 3.3 million jobs. The US, a nation with 12 times the population base of Australia, added 10.7 million jobs.

It could be argued that Australia’s job growth this century is more part time and less full time and that the jobs added are more likely to be baristas rather than family-supporting sheet metal worker type jobs. But this point can equally be made of job growth in other nations. Our performance stands clear.

Perhaps it was the counter-recession spending following the global financial crisis and that plunged the nation into debt. Perhaps its job growth associated with the Big Australia migration that now underpins employment in construction. Or perhaps its that we generate extraordinary taxable wealth from exports that is then spent on health, education and public administration.

Prosperity and lifestyle leave us vulnerable to the Trumpification effect

And if it is largely the latter (as I suspect is the case) then pictures of Port Hedland, the Port of Newcastle and the Port of Fremantle should be on our banknotes for their part in facilitating the export of iron ore, coal and grain.

Most job growth between 2000 and last year has focused on healthcare and social assistance (up 694,000), professional services (407,000) and construction (396,000). These three sectors alone have delivered a net extra 1.5 million jobs in 16 years.

What is the common denominator behind the three pistons driving Australian job growth this century? The answer is skills. To participate in the prosperity of modern Australia, a worker needs a university degree or technical training. The best thing aussie parents can do for their kids is to ensure they have some kind of technical skill or a university degree.

At the other end of the chart, it’s a different story. Between 2000 and last year the number of jobs in Australian manufacturing has dropped by 131,000 and the number in agriculture by 120,000. Manufacturing jobs are being offshored to Guangzhou courtesy of globalisation. And as for the agricultural sector: we are producing more output than ever, it’s just that we don’t need as much labour to reap the harvest.

Jobs in manufacturing and agriculture are largely unskilled or semi-skilled, whereas jobs in health and professional services are highly skilled.

A schism is opening up in the workforce and arguably in Australian society between the skilled and unskilled, between the haves and have-nots.

Add into the mix the effects of digital disruption brought about by robotics, artificial intelligence and financial technology, and all of a sudden job numbers start to contract in not just three sectors but in five or six. Job options contract. The mood of the nation shifts.

What does Australian social cohesion look like when perhaps a third of the workforce witnesses more job retrenchments than job appointments?

Continue this process for long enough with more and more sectors falling to the undeniable efficiencies of globalisation, mechanisation and digitisation, and a political backlash is prompted. In fact, this whole process leads to the Trumpification effect as displaced workers look for non-traditional solutions.

Consider the same numbers for the US. The data doesn’t exactly match up but the principle is the same. Between 2000 and last year the US workforce added 16.2 million jobs in 17 sectors but lost 5.6 million jobs in five sectors, leading to net job growth of 10.7 million. But this also means that for every job lost in the US only three new jobs have been created. The ratio for Australia is 12:1. When the job growth to job loss ration drops to the vicinity of three to one then the Trumpification effect is said to occur. But how close is Australia to this point? Are disenfranchised car assembly plant workers right now festering and fomenting suburban dissent? Consider the evidence from other countries. Job growth and loss in Canada follows much the same path as Australia, albeit at a slower rate.

Canada generates six new jobs for every job lost in manufacturing and agriculture. Britain also follows suit with most job growth being in health and most job loss being in manufacturing. The overall ration of job growth to loss in Britain is 5:1. France on the other hand, is very different. For example, the French report that since 2000 there have been job losses in five sectors, although all of these are variations on manufacturing. Most job growth in France has been in the scientific and technical, and public administration sectors.

For every job lost in manufacturing in France since 2000, less than three new jobs have been created elsewhere. France is mightily close to le points de Trumpification. By this measure, Australia is quite different to other nations. Yes, there are job losses, but job growth across a range of sectors offers displaced workers options for redeployment. Such options are less prevalent elsewhere. This, of course, augurs well for Australia for the time being, but it does raise the issue that workers are increasingly being marginalised by globalisation and digital disruption.

The arrival in Australia of US online retail giant Amazon, for example, could trigger the disruption of retail jobs. There are several response operations to the Trumpification effect. We should re-skill and upskill the workforce so retrenched sheet metal workers, for example, can be retrained to other jobs. Australian society is fairest and most productive when everyone believes they have a chance at sharing in national prosperity. At the 2001 census, 5200 workers were employed as photographic film processors. By the 2011 census this workforce had all but disappeared.

The most valuable workforce skills are resilience and adaptability. New technologies and new business models will continually reshape the workforce, meaning that only the most adaptive will survive and thrive. But even with an agile workforce there is still likely to be large scale displacement of workers in future and especially with the advent of, say, driverless cars.

What does Australian society look like when the means of production are controlled by an ever diminishing (in relative terms) proportion of the workforce hunkered down in the knowledge industries?

What this means is that we should focus on teaching science, technology, engineering and mathematics – the so-called STEM skills – although I would also add Mandarin and entrepreneurship. We should continue to build capabilities in individual resilience and we should further develop agility in the workforce. We need workers who embrace change as an opportunity to learn new skills and to create new relationships.

Parents should help their children develop soft skills such as self-confidence and sociability: future workers will need to adapt their skills and to demonstrate to others how they can add value. If you kid is special and precious and is used to having the world respond to their needs, then they will struggle in the workforce of the future.

At a societal level, we need to shift our culture entitlement to service. Identifying a problem and asking, “What’s the government gonna do about it” is not helpful. Rather, identifying a problem and asking how you can personally make a difference is helpful. Civic responsibility, volunteering, caring, paying taxes, being a good corporate citizen and giving rather than looking to receive are qualities we need to embrace and develop.

We need to shift our thinking to the extent that we admire people who have the energy, the chutzpah, the sheer ballsiness to create new businesses that employ people and pay due tax.

This civic-minded entrepreneurial skill is far more important to the future prosperity of the Australian people than the skill of playing cricket and football. I don’t want the social dysfunction that immediately proceeds the Trumpification effect to beset my beloved Australia. I want to live in an Australia where everyone has a chance at prosperity and where everyone is expected to and wants to make a contribution.